On August 19, 1989, Mark MacPhail, a former Army Ranger, worked for the Savannah Police Deparment. That night, with his wife and baby daughter at home, MacPhail was working as an off-duty as a security guard in a Burger King restaurant. When MacPhail learned of a man being assaulted in the parking lot, he intervened to defend the victim. Seven witnesses testified that they had seen Troy Anthony Davis shoot MacPhail, and two others testified that Davis had confessed to the murder. Davis, a black man, stood accused of killing MacPhail, a white police officer.

Some of the witnesses who testified at trial later recanted their sworn statements. Two of the jurors indicated that had they known 20 years ago of the facts that have surfaced since then, they would have voted differently. Nonetheless, some 20 years after he was originally sentenced to receive the death penalty, the State of Georgia ended Troy Davis’ life on September 21, 2011.

Sometimes, history entangles strange stories together. You see, back on June 7, 1998 James Byrd accepted a ride home from Shawn Berry, Lawrence Brewer and John King. Mr. Byrd knew the driver, Shawn Berry, from around town. But instead of taking him home, the three men took Mr. Byrd out into the country. They beat him viciously, urinated on him, chained his ankles to their pickup truck and dragged him for three miles. They then went to a barbeque. As you probably know, the incident took place in Jasper, Texas.

In one of those historical ironies, the State of Texas executed Lawrence Brewer on the same day Georgia executed Troy Davis. Brewer, a white supremacist, had previously served time for drug possession and burglary. He had apparently joined a white supremacist gang during this earlier prison term, and it was there that he met John King. When interviewed by the media the day before his execution and asked if he had any remorse, he said “As far as any regrets, no, I have no regrets. No, I’d do it all over again, to tell you the truth.”

As a lawyer, I think I understand the legal issues in most of these cases, and it’s hard for me to avoid the notion that the death penalty is constitutional. There are also a number of practical issues involved, like the question of deterrence and the relative cost of life imprisonment versus the total costs of carrying out the death penalty. One of those practical issues is the remarkable disparity in the racial application of the death penalty. There’s also the question, in fact the probability, that we have executed several people who were innocent of the crimes of which they were convicted. But I don’t think that answers the question, the bedrock question I’d like us to consider this morning: what kind of people do we want to be?

The scriptural witness in this regard is somewhat ambiguous, forcing us, as Scripture so often does, to struggle with the text and its meaning. Proponents of the death penalty find solace in the commandment of Leviticus: “Whoever takes the life of any human being shall be put to death” (Leviticus 24:17). (It’s worth noting, however, that the Old Testament similarly provides for the execution of those who works on the Sabbath (Exodus 31:15) or for one who curses one’s parent (Exodus 21:17) and even for a rebellious teenager (Deuteronomy 21:18-21).)

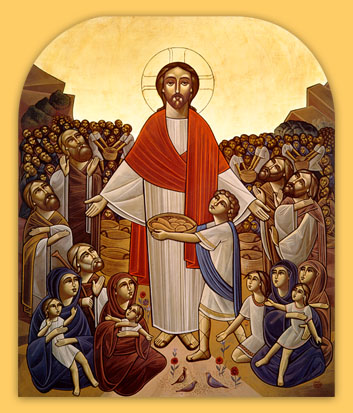

Those who oppose the death penalty can look to the notion that God has reserved vengeance for himself (Rom. 12:19). We find in the Biblical story of the first murder that God spared Cain’s life, although Abel certainly seems like an innocent victim. Chapter 8 of John’s Gospel records the only time our Savior’s encounter with capital punishment in the case of the woman caught in adultery; and Jesus put a stop to it.

It’s worth observing that there are good people, and there are people of faith, on both sides of this issue. As so often happens, we find that we must struggle with the biblical text on this issue. I think that’s a good thing, because the Bible isn’t a book of recipes that will teach us how to prepare a good life, nor is it an encyclopedia where we can go to look up the “right” answer. In Holy Scripture, God speaks to us in a collection of stories, a narrative about how people struggle to find their sanctification and how we struggle to find ours.

Three overarching themes, however, strongly suggest to me that capital punishment is the wrong answer. The first of these is an understanding of what it means to be human. We are told that we were made imago Dei, “in the image of God.” That probably doesn’t mean that our elbow looks like God’s elbow. But I think it means that all of us have some spark of the divine within, no matter how well we try to hide it. In other words, we are all instances (no matter how blurred) of something sacred and holy.

Secondly, we have the Biblical meta-narrative of God’s reaching again and again to redeem people, not because of their merit but because of His love. This happens over and over in the Bible, often enough that I believe God is trying to tell us something. We see it in the story of Cain, in the Exodus (which remains the overarching narrative for the Jewish people), in the story of David, and in the story of Christ’s calling St. Paul. Jesus preached “Do not judge, so that you may not be judged.” (Matt. 7:1.) While I’m not smart enough to have considered all of the implications of that commandment, I think at a minimum that we are not to judge the content and character of another man’s soul. God knows who can be redeemed, and I do not.

Finally, I oppose the death penalty because I honor the Christian virtue of hope. I am hopeful that God can redeem the even the shame of the murder of James Byrd, and the horror Lawrence Brewer’s unrepentant racism. I am hopeful that God’s love can reach into Brewer’s life, and into mine. I believe in “the means of grace and the hope of glory.” I think capital punishment reflects a despair at the possibility of Christ’s redemptive love reaching into the very darkest places of the human heart, and I am compelled to reject that.

In the final analysis, I think the real question is one posed by Sister Helen Prejean: “The profound moral question is not, ‘Do they deserve to die?’ but ‘Do we deserve to kill them?'” I pray the answer is no, just as I pray for Mark MacPhail, for James Byrd, for Troy Davis and Lawrence Brewer.

Shabbat Shalom,

James R. Dennis, O.P.

© 2011 James R. Dennis

Heavenly Father, we thank you that by water and the Holy Spirit you have bestowed upon these your servants the forgiveness of sin, and have raised them to the new life of grace. Sustain them, O Lord, in your Holy Spirit. Give them an inquiring and discerning heart, the courage to will and to persevere, a spirit to know and to love you, and the gift of joy and wonder in all your works. Amen. You are sealed by the Holy Spirit in Baptism and marked as Christ’s own for ever. Amen. The Book of Common Prayer.

Heavenly Father, we thank you that by water and the Holy Spirit you have bestowed upon these your servants the forgiveness of sin, and have raised them to the new life of grace. Sustain them, O Lord, in your Holy Spirit. Give them an inquiring and discerning heart, the courage to will and to persevere, a spirit to know and to love you, and the gift of joy and wonder in all your works. Amen. You are sealed by the Holy Spirit in Baptism and marked as Christ’s own for ever. Amen. The Book of Common Prayer.