Here’s the link to the video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IwuOJMirg6U&t=69s

Here’s the link to the video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IwuOJMirg6U&t=69s

“It is to such as these that the Kingdom of God belongs.” (The full text of our readings can be found here.)

In the name of the Living God, who is creating, redeeming, and sustaining us. Well, good morning, everyone, good morning.

You know, I grew up out in West Texas. And when I was a young man I engaged in some pretty risky behavior. Now and then I would drink too much. And I liked fast cars, and liked to see how fast they would go. And I would date these girls..well, if you’ve ever been to a rodeo…well, they were barrel racers. And I want to assure you that they are, every single one of them, loco. I mean not average plain old crazy…they were fancy crazy, with glitter and everything, and some of them were mean, too.

So, I know what it means to walk into a room full of trouble. But when you walk into a church full of people you really don’t know all that well, about a third to half of whom have been divorced, including the guy in the pulpit, to preach a sermon on the topic of divorce, well, that’s next-level hazardous; that’s right on the border between silly and imbalanced. But here in the diocese of West Texas when there’s a really foolish, precarious situation, one that really no one with good sense would mess with, I’m the guy they call. Because, as we all know, fools rush in where angels dare not tread.

So, let’s turn to this passage of Scripture, a passage that has been poorly understood, horribly misused, and cruelly interpreted. Let’s try to look at this story in context, beginning with the historical context.

The first thing we need to understand is that whatever sort of divorce Jesus was talking about, divorce in first-century Palestine had very little to do with the sort of divorce we may have had some experience with. Ancient Israel, like most of the ancient world, was patriarchal, and wives were regarded as the property of their husbands. Thus, while a husband could divorce his wife, the wife had no reciprocal ability to divorce her husband. Marriages were not based on our current notions of romantic love between two persons but on considerations of property, status, and honor between two families. If a husband did divorce his wife, she and the children would probably end up penniless, begging, or something worse

Now let’s look at this story in the textual context, in the context of a story that Mark is telling us. This discussion takes place when Jesus is answering certain questions he’s asked by the Pharisees, asked to test him or to trap him. In this passage, Jesus isn’t asked about how God feels about divorce, or even how Jesus feels about divorce. Rather, they ask Jesus a question they already know the answer to—they ask him what the law says. Now, the Pharisees were a lot of things, but mostly, they were a group devoted to understanding, preserving, and interpreting the law. So, they didn’t come to Jesus with a genuine question, but rather with a snare.

Now let’s look at this story in the broader Gospel context about Jesus’ relationship with the law. Everything we know tells us that Jesus’ relationship with the law was….well, complicated. When Jesus’ disciples were accused of breaking Jewish law by plucking grain and eating it as they walked along on the Sabbath, Jesus responded that David and his companions ate the consecrated bread that the law reserved for the priests. When the Pharisees caught a woman in adultery and were going to stone her as the law directed, Jesus told them that the one without sin should throw the first rock. The Pharisees constantly criticized Jesus for healing on the Sabbath, which he did so regularly one might conclude that Jesus was looking for trouble. And I think he was: I think Jesus was looking for what the great John Lewis called “Good Trouble.”

It seems to me that in this morning’s reading, Jesus is doing what he did so often. I think he was forcing us to overcome our legalism and look more deeply at the principles that underlie the law, and to look more deeply within ourselves. Jesus tells us the problem isn’t with our legal situation but with our medical situation—with the hardening of our hearts. He says Moses only gave you the commandment concerning divorce because of the hardness of your hearts. If you’ve ever walked through a divorce with one of the parties, or with a couple, you know how hard our hearts can get. If you’ve ever watched children go through a custody battle, you know how hard our hearts can become.

Rather than involving himself in a debate about the circumstances in which divorce might be permissible, Jesus (as he so often did) calls us to examine the first principles behind marriage. Part of that first principle Jesus turns to is the story of creation: we were not made to be alone; we were made for life in common, a life in love.

We know of many reasons why a marriage can fail: infidelity; alcohol and substance abuse; workplace stress; financial stress; mental illness; disagreements over parenting styles; religious differences; physical and mental abuse. Like the psalmist says, we’re “just a little lower than the angels.” Very rarely have I encountered a situation where one party was completely to blame and the other party was completely blameless in the failure of the marriage. Divorce can leave behind emotional and spiritual wreckage. And sometimes I have seen circumstances where ending the marriage was the least wrong answer two people had available to them. Because whatever the marriage covenant is, I’m pretty sure God didn’t intend it to be a suicide pact.

I have known way too many people, mostly women, who were berated and shamed by churches and church leaders when their marriage ended in divorce. And I don’t know how Jesus would feel about all the reasons modern marriages break down. But I do know how Jesus felt about our habit of judging each other and I know how he felt about cruelty. I know that, for all of us, hardness of heart is a spiritual issue. Our lives can become so very isolated, so very disintegrated, so very fragmented.

Today’s Scripture isn’t really about the legality of our justifications for divorce. It’s about how we overcome our natural hard-heartedness and learn to live lives that are full of compassion and vulnerability and courage. It’s about learning to live into God’s dreams for the world rather than our failures and disappointments. That’s the only way we’ll discover the real intimacy God intended for us and the real blessing of a life spent in gratitude and the joy of delighting in each other. I’m pretty sure if we start off in that direction we might find the kingdom of God. That’s the kind of life I want, and I hope you want it, too. Amen.

James R. Dennis, O.P. © 2024

Posted in Uncategorized

Tagged adultery, Anglican, Bible, Disciple, Bible, Christianity, divorce, Gospel of Mark, Jesus, marriage, Moral Theology, Pastoral Care, Spirituality, Theology

But the thing that David had done displeased the Lord, and the Lord sent Nathan to David. (The full readings for today can be found here.)

In the name of the Living God, who is creating, redeeming, and sustaining us. Good morning, good morning. Now, some of y’all know that my family came from out in West Texas, and that’s where I grew up. And y’all might find this surprising, but I was not always the saintly person you know today. No, I was not always the shining angelic light you see here on Sunday mornings. My misbehavior wasn’t usually all that serious: maybe I was cruel to my brothers, or acted selfishly, or took something that didn’t belong to me. And every now and then, the fire trucks would have to come to our house, but that’s another story.

So, when I would fall short of my parents’ expectations, my father would pull me aside and look me in the eyes and tell me, “Son, that’s not the cowboy way.” And without fail, I would crater. I would dwindle away and shrink to about 2 inches tall because I knew I had failed to live the way my family had lived for generations. And come to think about it, my father was not unlike one of the Old Testament prophets, not unlike Nathan in today’s story. And when my father had these little chats with me . . . well, I knew I had been prophesied to.

So, our reading today continues the story we began last week. So, maybe we ought to review just a bit. Our story began when David was king over Israel, in the springtime as scripture tells us, “when kings go out to battle.” But David, he didn’t go out to battle, and we’re not told why, but David let others fight his battles for him. David looked down from his roof and saw a beautiful woman bathing herself, and he wanted her. Even knowing she is the wife of one of his commanders, who is off fighting his battles for him, he wanted to have her.

And David took her, and lay with her and she became pregnant. And then, and this is hard to imagine, it gets worse. First, he tried to cover up his affair by bringing Uriah home from the war. When that didn’t work, he arranged to have Uriah killed in battle. And that gets us up to where our reading begins this morning. After arranging for her husband’s death, David brings Bathsheba into his house, marries her, and she gives birth to his child.

I know this is a shocking story and we are all clutching our collective pearls. Within about a month, David has managed to break almost every one of the Ten Commandments. I mean, a political figure, a religious leader, involved in a sexual scandal and then trying to cover it up? Thank heavens we don’t have to deal with that sort of thing anymore.

So, I want to stop there and do a bit of a theological reflection on this man, this king, David. We all remember the story of David killing the giant Goliath who had been mocking the armies of Israel. The very first words we hear out of David’s mouth in that story are: “What will you do for the man who kills this Philistine?” In other words, what exactly is in it for me? Then we have him engage in an affair with Bathsheba, and engage in all sorts of sordid behavior to try and cover it up, including what amounts to basically murder. Our Jewish brothers and sisters have a complicated theological term for this sort of person. They would tell us that David is acting like a schmuck, and they would be right.

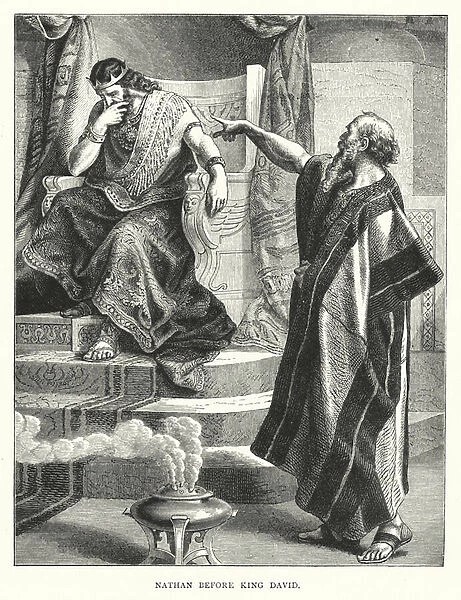

So, our translation this morning tells us that the thing that David had done displeased the Lord. That translation sort of softens the original text; this is not exactly what the original Hebrew says. In Hebrew, the text reads that the thing David had done was evil in the in eyes of the Lord. And so, the Lord sends the prophet Nathan to speak to David, to tell him that he’s been acting like a schmuck, to tell him “that’s not the cowboy way.”

So Nathan goes to David, and Nathan tells him a little story: he tells him a parable about a poor man and a rich man who stole the poor man’s only lamb. And to his credit, David hasn’t completely lost his sense of right and wrong. David says, “As the Lord lives, the man who has done this deserves to die.” So, David can see the moral failure in the story; he just can’t manage to see it in the mirror.

This gets me to one of the first observations I want to make about sin. Sin can act like a kind of moral cataract, obscuring our ability to clearly see our own situation and the nature of our actions. Like King David, self-delusion is one of my superpowers. And because of the nature of sin and its ability to blur our vision, from time to time we all need a prophet Nathan to help us see ourselves more clearly.

And Nathan shows David some of the consequences of what he’s done. He says because you’ve taken the life of Uriah and taken his wife, the sword will never leave your house. And God tells him, I will raise up trouble against you from within your own house. God says, you did these things in secret but I will do them openly. And David comes to realize that he has sinned.

So, I think this story teaches us a few other things about the nature of sin. First, we think we can control it, but we can’t. The outcome of sin is unpredictable. Sin operates sort of like the science of forensics. When the bullet enters the body, it enters through a tiny hole, but as it travels through cartilage and bone it flattens and spreads and the exit wound is much larger and jagged.

Secondly, there are two people who haven’t done anything wrong in this story: Uriah and the child of David and Bathsheba’s union. Both of them will die. It would be nice if the only people who suffered because of sin were the guilty, but that’s not the way this world works. Sin has a gravitational pull and draws the innocent into it. Sin is unstable, and collateral damage is just part of its capricious nature.

Third, we hope that the harm done by our wrong will be comparable to the wrong done. Again, that’s magical thinking, an infantile hope. Because of sin’s unstable nature, the consequence of sin can sometimes be vastly disproportionate to the level of wrong done.

And the last observation I’ll make about sin comes from one of my favorite novels, The Great Gatsby. Fitzgerald wrote: “They were careless people, Tom and Daisy – they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.” The point is this: in order to great harm, we don’t actually have to intend some evil plan; great harm and great suffering can result from our simple carelessness.

The more we understand about the nature of sin, the more perilous this world can seem, as though we were walking through a moral minefield, with nowhere safe to step. But there is a place we can go. There is a balm in Gilead, and there is mercy, and it is plentiful. We can trust in the practice of confession and absolution. We can turn to the Nathans in our lives, perhaps our confessors, perhaps our spiritual directors, perhaps a priest or a close friend. We can find all those right here at St. Mark’s Episcolopolus Church. And in a few moments, we can come to this altar, to take a bit of Jesus into our lives, maybe lay down some of our burdens there. And in that sacrament of repentance and forgiveness and renewal, we can start over again. Amen.

James R. Dennis, O.P. © 2024

But when he noticed the strong wind, he became frightened, and beginning to sink, he cried out, “Lord, save me!” Matt. 14:30 (The full text of the readings can be found here.)

In the name of the Living God: by whom we are being created, redeemed, and sustained.

As a boy in West Texas, I grew up as the oldest of four sons. Now, that was in the 60s, and back then, we went through a lot of uncertainty, a good deal of ambiguity. But there’s one thing we all knew with absolute mathematical precision; we knew it to a moral certainty. We knew it because every boy in West Texas knew it. We were sure that if a horny toad shot blood into your eyes, we knew that you would go blind.

So one morning, early in the morning, I woke up to find that my brothers had tied me to my bed. Like Gulliver, these Lilliputians had bound me where I lay, and I knew that nothing good could come of this. But my predicament got even worse when my brother Patrick, my no-good brother Patrick, took out a shoebox containing at least a dozen big fat horny toads. With glee in his eyes, he dumped them onto the bed where I was tied down and screaming like a banshee. Now, I’m not saying that my brothers were intentionally trying to blind me, but they were at least wildly indifferent to the possibility that I would end up sightless. So, I understand exactly how Joseph felt when his brothers threw him into a pit and sold him into slavery in Egypt. And I was sorely tempted to preach on that today, but the Church has given us an even better story.

Oh my, what a story. So today, we hear the story of a man named Peter who is willing to leave his relative comfort and security because he hears the call of Jesus.

If you know anything about my spiritual life, you know that I love Peter. He is my favorite biblical blunderer—overenthusiastic, and terribly underprepared. He is full of bravado and bluster and he clumsily rushes in where angels fear to tread. I think he really wants to follow Jesus, but most of the time, he really doesn’t have a clue about what that might look like. You know, now that I think about it, he’s a lot like…me.

It’s important for us to look at this story in context. This passage follows the feeding of the 5,000 in a deserted place, in the wilderness. Now the writers of scripture use two ways to signal a time and place of trouble and anxiety and danger. They talk about the wilderness, and they talk about the sea. And in this Gospel passage, Jesus has just left the wilderness, and the disciples find themselves on a stormy sea. So, you know there’s going to be some trouble.

One of the consistent metaphors used throughout the Old and New Testaments is the image of the sea as representing trouble or difficulty. These waters represent the nothingness before creation, in the Hebrew the tobu wa-bohu. The sea was perceived as the vortex around which danger and chaos and evil spun. So, in today’s Gospel, we find Jesus calling the disciples, not away from the storm, but into it. In fact, Jesus sends the disciples into the boat while he dismisses the crowds and goes to pray. Jesus goes to the mountain, like Moses, to encounter the God of Abraham. Thus, while he retreats to the mountains, he compels the disciples to face the sea of chaos. Literally translated, they are being tormented by the waves. Jesus compels them to confront their own frailty, their own vulnerability.

This story reminds us of another story in Matthew’s Gospel, in the eighth chapter. If you’ll remember that passage, Jesus was sleeping through the storm while the disciples cried, “Save us, Lord, for we are perishing.” And if you’ll recall, that story ends with the disciples wondering what kind of man Jesus is, if even the wind and the water obey him.

So, in today’s reading, it’s worth noting that the disciples have been out in this storm, on the water, for a long time. They’re sent away before evening, and they don’t see Jesus again until early in the morning. So, like many of us, they’ve been struggling to stay afloat for a good while. It’s not really the storm that frightens them, but they are terrified when they see Jesus. I love the nonchalant way the Gospel writer reports, “he came walking toward them on the sea.” Matthew records it as matter-of-factly as if he were saying that Jesus scratched his head or sat down to eat a tomato sandwich.

The disciples, as is so often the case, fail to recognize Jesus. And maybe, just maybe, it’s their fear that keeps them from knowing Jesus, just like our fear sometimes keeps us from seeing Jesus when he’s right beside us.

While the disciples are initially afraid that they are seeing a ghost, Jesus reassures them it’s him. And our translation really doesn’t do justice to Jesus’ words of comfort. In fact, this is a bad translation; it’s a terrible translation. In the original Greek, Jesus’ announcement is more sparse, succinct, and significant. In the Greek, Jesus says “Ego eimi.” That phrase, I Am, is the name of God, the name he gave Moses as he told him to confront Pharoah. And so, Jesus assures them: “I Am.” He takes them back all the way to the God of Abraham and Moses, reminding them of the presence of God even on this storm-rocked sea.

And so, Peter sort of invites himself to join Jesus on the water. He calls Jesus “Lord,” but I’m not sure he understands exactly what he’s saying. Jesus is Lord, Lord over the deep and troubled waters, Lord over the wind and waves, Lord over the storms and all the destructive powers that seek to overwhelm our lives.

This is why I love Peter: he is so eager and yet, not quite ready. And he joins our Lord on the water and for a moment….the laws of nature and gravity are suspended. I suspect that, for just a moment, the angels stopped their singing and all heaven held its breath. And then, Peter began to notice the strong winds around him and he began to sink. And, whatever else you can say about Peter, at least he has the presence of mind to know where to turn in trouble. He turns to Jesus. He cries out, “Lord, save me.”

And when Jesus returns to the boat with Peter the wind dies down and the disciples all acknowledge that Jesus, the Jesus who walks across the storm and calms all our troubled seas, is the Son of God. And I don’t think we should judge St. Peter too harshly, in fact, I don’t think we should judge him at all, because he embodies one of the fundamental principles of the Christian life: we are going to fail. We fall down five times, and through God’s grace, we get up six.

Changing our lives is hard. It was hard for Peter and it’s hard for us. If we want to live for Christ, live whole-hearted lives, it’s going to take some time, and we’re going to make mistakes. Living with courage and hope and taking chances means we’re going to fail sometimes, and we need to be prepared for that. And yet, God—the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, who constantly reminds us “I Am”— is always stronger than the sum of all our fears and failures.

Following Jesus is no assurance of smooth sailing. Being disciples does not shield us from the hard knocks of life and death. In fact, the biblical witness would tell us something quite to the contrary: we are assured of the storm.

You see, like St. Peter, God wants more from us than lives of safety and stability. God’s dreams for the world are bigger than that. God has called us to be explorers on an adventure: seeking God in unlikely places and pointing out His presence when others cannot see it. God had wonderful dreams for Peter, and has wonderful dreams for us, too. And so, we join him in stepping out of the boat, sinking sometimes, but always proclaiming the presence of God in the storm. Amen.

James R. Dennis, O.P. © 2023

Posted in Uncategorized

Tagged Anglican, Bible, Disciple, Christianity, discipleship, Episcopalian, Gospel of Matthew, Jesus, Spirituality, Theology, Trust

“Woman, why are you weeping? Whom are you looking for?” (The full readings for this morning can be found here.)

In the name of the living God, who is creating, redeeming, and sustaining us. Well, good morning, good morning. And, because we haven’t been able to say it during those long 40 days of Lent: Alleluia!

Don’t you hate it when you lose something? It’s very frustrating, it’s unsettling. Say, you have something very precious, or something terribly dangerous, and you lock it up and put it away where no one can get to it. You hide it, or seal it up, or bury it, and when you go back, it’s not there. You search and search, but it’s just not there anymore. But, I’m getting ahead of myself.

I want us to imagine the desperation of these disciples, particularly Mary Magdalene and the women who go to anoint Jesus’ body. They had lost just about everything you could lose. Some had betrayed him, some had denied him, many had run away, and almost none of them could bear to watch this horror show. They had lost their dreams of a life with God, their vision that finally someone was going to do something about the Romans and their brutal occupation. They had lost their hopes for a better world, and many of them lost their self-image, their idea of who they were. And so, these women come to anoint their dead friend, to honor their dead. As Henry Nouwen wrote, “Compassion asks us to go where it hurts…” Now, I don’t think those women went to the grave that morning out of a sense of religious obligation, or some concept of duty. I think they went there out of love for their friend.

Now, we humans have known something for a very long time. We have known it ever since we crawled or loped out of the savannah, ever since those prehistoric people left their handprints on the Cueva de los Manos in Spain. We have known that “dead is dead.” Science teaches it, our experience teaches it, and our feelings of loss teach it. Dead is dead. Our broken hearts have always instructed us about the finality of death. Death is the end of the story. Or, is it?

Today’s gospel calls that assumption into question. As these women go to mourn their losses, they find that the stone has been rolled away and the tomb is empty. Don’t you hate it when you’ve put something away for safekeeping and then it’s missing? And after the other disciples have confirmed that Jesus’ body is gone, Mary remains at the tomb weeping. And she doesn’t recognize Jesus at first. Grief is like that, clouding our vision and consuming our ability to focus on anything but loss. And it’s not until Jesus calls her by name that she recognizes him. My hope, no, my prayer for each of us is that we can hear God calling our names, calling us out of grief and loss and into new life.

Jesus then asks her a very pointed, and very important, question: “Whom are you looking for? In our world of heartache, loss, death, and empire, it takes a good deal of courage to go looking for Jesus. It takes a good deal of hope and strength to entertain the notion that death might not be the end of the story. Love is like that, you see. Love always goes looking for the beloved. Even when it’s scary, even when there are Roman guards there, even when it seems hopeless—love goes looking.

So, I want you to look here at the genius of John’s gospel. If you were with us for the Good Friday service, you’ll remember what John said. “Now there was a garden in the place where he was crucified, and in the garden there was a new tomb in which no one had ever been laid. And so, because it was the Jewish day of Preparation, and the tomb was nearby, they laid Jesus there.” Our story this morning is also set in that same garden.

If you were with us for the Vigil, you heard that story from Genesis of the very first day, the story of light coming into the world. So, I want us to look carefully at what that masterful poet John is telling us in his gospel this morning. John says these events took place “Early on the first day….” The first day. These events took place in a garden. The story of our creation takes place in a garden. This is no accident. There are no coincidences in John’s gospel. I think John is trying to tell us that the story of Jesus’ resurrection is the story of God recreating the world. It’s the story of Jesus “making all things new again.”

Now, the forces of empire knew exactly where they had put Jesus. He was sealed in a tomb, safely locked away where he could not cause them any trouble. In this story, the might of empire is represented by the soldiers guarding the tomb. Look at the reversal that takes place when they are confronted with the power of resurrection, the power of new life. John says, “For fear of him the guards shook and became like dead men.”

God is in the business of creating life where there was no life before. St. Paul notes that the grave has lost its finality, writing: “O death, where is thy sting?” But I probably prefer the formulation of that fine mystic, the English poet John Donne, who said:

Death, be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so;

For those whom thou think’st thou dost overthrow

Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me.

Death is not the end of the story. It’s not even a period, not even a semicolon. Death is nothing more than a comma, a brief pause. You see, when Jesus walked out of the tomb, he didn’t come out alone. God’s love escaped from the tomb, escaped from the grave where the forces of empire tried to contain it.

So, we come back to these stories, these same stories, year after year at about this same time. The church calls them the stories of Jesus’ passion and resurrection. But in a broader sense, they are something more: they are love stories. In fact, they are our love stories. They are stories of God’s love for you and me, of God’s love for humanity.

This is our theology of hope; this is why we call ourselves an Easter People. Our gospel this morning teaches us that the forces of empire do not win. The powers of fear and intimidation and violence do not prevail. Death and grief do not have the last word. Darkness and the forces of hell do not win. Love always wins. Always. And even though we go down to the grave, we make our song: Alleluia, Alleluia, Alleluia!

James R. Dennis, O.P. © 2022

Posted in Uncategorized

Tagged Anglican Dominican, Christianity, Creation, Easter, Gospel of John, Jesus, Religion, Resurrection, Spirituality, Theology

He is not here; for he has been raised, as he said. Come, see the place where he lay. (The full readings for today can be found here.)

Good evening, my friends, good evening. And welcome to the Great Vigil of Easter.

Did you notice that opening line of that very first reading? It’s such a fabulous first line, a cardinal statement: “In the beginning when God created the heavens and the earth, the earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep, while a wind from God swept over the face of the waters. Then God said, ‘Let there be light’; and there was light. And God saw that the light was good; and God separated the light from the darkness.”

But we might well wonder, Why is the Church giving us that story this evening, as we celebrate the great vigil? What does this have to do with Easter—with the empty tomb? It’s almost as if the Church were trying to tell us something, as if the Church were offering a glimpse into the nature of God through the lens of these readings. I think the Church is trying to give us some insight into God’s professional life, God’s business. You see, I think God is in the business of creating life where there was no life before. And there’s only one reason for that sort of creative impulse, that need to form and shape something new. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

So, I want us to imagine the state of mind of the disciples, particularly these women, going to anoint Jesus’ body for his burial. Not only have they witnessed the brutal horror of Jesus’ death, not only have they lost their friend and teacher, but they’ve also seen a dream die. They had dreamed of a life with Jesus, of a life filled with God’s love; they had dreamed of a better world. So they went to the tomb to honor their friend, to honor their loss, to honor the dead.

But they didn’t find any death there, because our God is not the God of the dead, but of the living. Our God, as we said earlier, is in the business of new life. Our God is in the business of calling light out of the darkness, of creating new life out of nothing more than His love.

We see that new life happening this evening, right before our eyes. God is on the loose again tonight at St. Christopher By the Sea, doing that God thing. God is about to make a new thing, another Genesis story, in the baptisms of Addison and Wayne. And, while we don’t know yet what paths they will walk down in their lives to come, we know who will always walk with them.

Looking back to the readings tonight, I’m pretty sure that the forces of empire were certain that the story of Jesus was over. In fact, they were certain he was not only dead, but buried. But God, like love, is never static; neither God nor love will be contained. And I want to suggest to you that something more than Jesus escaped from that grave—pure love rolled away the stone, unadulterated love walked out of that tomb, and love told those dear women that he would meet them again in Galilee.

Many of us have tried to keep God in a box. We try to create a spiritual ghetto—over here is where I keep my work life, and over here is where I keep my family stuff, and this box here is where I keep my religion. That box we try to keep God in, well, it’s nothing more than a grave, a tomb. And if today’s Gospel teaches us anything, it teaches us that God will not stay where we put Him. This is our hope; this is why we call ourselves Easter people, my friends. He is not dead; he is risen. Alleluia!

James R. Dennis, O.P. © 2022

Posted in Uncategorized

Tagged Anglican Dominican, Christianity, Easter, Episcopalian, Gospel of John, Jesus, Religion, Resurrection, Spirituality, Theology

In that city there was a widow who kept coming to him and saying, `Grant me justice against my opponent.’ Luke 18. (The full readings for this morning can be found here.)

In the name of the Living God, who is creating, redeeming, and sustaining us. Well, good morning, good morning. It’s good to be with you again here at St. Michael’s. And many thanks to Brynn and all of you for your generous hospitality.

So, this morning in the lectionary, the Church offers us this story which is sometimes called the parable of the unjust judge. And this passage of the Gospel reminds me of one of my favorite stories about the religious life. Several years ago, there was a young woman who became a nun. And she made her vows and entered the convent. Now the rules of this particular Order required that she be cloistered and keep silence, although every ten years the sisters were allowed to say two words. So, for the first ten years, she was assigned to make the beds. And she changed the sheets, and washed them, and made every bed throughout the monastery. And at the end of that ten years, she went to the Mother Superior and said, “Bed hard.” Well, the next ten years, she was assigned to the kitchen. And she peeled the potatoes and cooked the oatmeal and cleaned every pot in that monastery. And at the end of that ten years, she went to the Mother Superior and told her, “Kitchen hot.”

After ten long years she was next assigned to clean the bathrooms. And she washed every sink and bathtub and scrubbed every toilet they had. And at the end of that ten years, she went to the Mother Superior and said, “I quit.” And the elder nun looked at her and said, “Good. You haven’t done anything but nag me since you got here.” Contrary to that story, and today’s gospel, I don’t think prayer has much to do with nagging God.

And we may be a little confused by this parable, or by many of them. The Hebrew word for parable is mashal, which carries with it connotations of a story, or an allegory, or a riddle. And many of these parables may leave us scratching our heads, including the one this morning, but that’s their function. They’re kind of like a picture frame that is intentionally hung so that it’s not level, so that we’ll have to really think about and puzzle over what’s portrayed. These parables are meant to make us think, to examine, and to turn an idea over in our minds until we come to a deeper understanding of it. And the broader question that I think Luke wants us to look at is how do we think prayer operates, and what does faithful living look like in a fallen world?

So, let’s take a deeper look at this parable and see what it offers us. Jesus begins his story: “In a certain city there was a judge who neither feared God nor had respect for people.” Oh, I’ve been to that city. And I’m pretty sure that I know that judge. I was a lawyer for a very long time, and on more than one occasion, I ran across that judge who did not fear God nor respect people. And without revealing too much about this judge, I can tell you that the county seat is Beaumont. Now, I should have known there was going to be a problem because in French the name Beaumont means “beautiful mountain.” Have y’all ever been to Jefferson County? Well, it’s not beautiful, and there’s no mountain.

Seriously, if you’ve ever met someone like that—someone who doesn’t fear God and doesn’t respect people—you know how truly frightening a person that is. And I don’t think for a moment, Jesus is trying to tell us that God is like that. The God we worship loved and respected humanity, embraced all sorts of people, prayed regularly, and his blood watered the hill we call Golgotha. I want to circle back to the contrast between God and this unjust judge in just a moment, but first let’s look at one of the other characters in the story.

When we examine the widow in this parable, we remember the biblical direction about taking care of widows because in that world they were fragile and vulnerable. And yet this widow doesn’t seem vulnerable at all. She constantly goes to the unjust judge asking for justice against her opponent. Some translators tell us the better translation is “give me revenge.” And we might re-think our notion of her as fragile when we realize that the judge is actually being worn out by this woman.

So, is Jesus actually telling us that the real secret to a rich prayer life is becoming a bother to God, pestering the Almighty until He just gives in? Somehow, I don’t think that’s the point, especially since Jesus is on the receiving end of so many of our prayers. Now, there are some folks, and a few preachers, who will tell you that if you close your eyes real hard, and give money to the church, and believe just right, God will give you anything you ask for—as if the Almighty were some sort of a cross between a celestial ATM and a divine Santa Claus. We have a name for that sort of theology. We call it “heresy.”

I think Jesus is talking to us about two things. First, he’s telling us not to lose heart. And it’s so easy in this world to lose heart. There are unjust judges everywhere. Our political discourse has been reduced to the snarkiest common denominator. And in our prayer life, help never seems to come as quickly as we’d like, if it comes at all. And if we view prayer as a transaction, we might lose heart all the more quickly. I don’t think our prayer life is like a Vegas slot machine, where if we just keeping putting in enough tokens, we’ll hit the jackpot.

I do think, however, it’s like another bible story, one we didn’t hear today but I’ll bet you know it. I think our prayer life is a lot like the story of Jacob. And you’ll remember that Jacob was trying to come back home, knowing that his brother Esau was furious with him and he’s worried that his brother is coming to kill him. And that night a man comes to Jacob and wrestles with him. And the scripture is unclear about whether Jacob is wrestling with a man, or an angel, or with God himself. The two of them wrestle all night. And although in the struggle Jacob’s hip is thrown out of joint, he tells his opponent, “I will not let you go unless you bless me.”

Our prayer life is like holding onto God, struggling with God all night, even when we are injured in the struggle. It is a stubborn insistence on a blessing, oftentimes a blessing we do not yet understand. As Saint Paul says, we train ourselves to be persistent whether the time is favorable or unfavorable. We will wrestle all night, holding on for that blessing. We will lift up our eyes to the hills, knowing that our help can only come from the Lord. And if we remain obstinate, if we stubbornly cling to God even when our strength is failing, the Son of Man will return to find that we are a faithful people. Amen.

James R. Dennis, O.P. © 2022

Posted in Uncategorized

Tagged Anglican, Bible, Disciple, Bible, Christianity, Dominican Order, Episcopalian, Gospel of Luke, Jesus, Prayer, Spirituality, Theology

James R. Dennis, O.P. © 2022

Posted in Uncategorized

Tagged Anglican Dominicans, Baptism, Bible, Christianity, Episcipalian, Episcopalian, Gospel of Mark, Jesus, John the Baptist, Religion, Sacraments, Theology

The full readings for today can be found here.

Then they came to Capernaum; and when he was in the house he asked them, “What were you arguing about on the way?” But they were silent, for on the way they had argued with one another who was the greatest.

In the name of the living God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Then they came to Capernaum; and when he was in the house he asked them, “What were you arguing about on the way?” But they were silent, for on the way they had argued with one another who was the greatest.

In the name of the living God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

You know, sometimes I read Mark’s Gospel and I just cringe at the disciples. That’s probably not the right kind of thing for a preacher to say about these men who the Church would later call “saints,” but these guys are the worst. I mean, here Jesus is, trying for the third time in this 9th Chapter of Mark, to tell them—that he will be betrayed, that he will suffer and be killed, that he will come back from the dead. And all they want to do is argue about which one of them is the greatest. These guys are numbskulls, they are narcissistic, self-absorbed mercenary chuckleheads who don’t understand anything about the Gospel or Jesus or the kingdom of God or anything. And what really infuriates me about them, the really exasperating part about them, is that they are so much like me.

And it makes me wonder, what is God trying to tell us as we bicker and argue on the way? What message are we missing as we struggle for success, power, or achievement?

Admittedly, the world teaches us to love these things from a very early age. We have to get the best grades, so we can go to the best colleges, so we can get the best jobs and make the most money. In sports, we are consumed with who’s the best of all time. And we want to know who won the best picture, to stay in the nicest hotels, to drive the best cars. And we want to name among our friends those who are powerful, influential, and important.

I’m reminded that in February of 1964, Muhammad Ali proudly announced to the world, “I am the greatest.” He said, “I am the greatest.” I think I’ll circle back to that idea in a bit.

Things weren’t so different back in Jesus’ time. Sociologists have described 1st Century Palestine as an honor/shame culture. In this sort of culture, you would find honor if a person of great wealth or great importance came to your home or became your associate. On the other hand, you would be shamed if a person of low social standing came to your home for dinner or befriended you.

Now, in that world, children were of no social standing or significance at all. They were completely dependent, and vulnerable in the world around them. And so, Jesus continues to try to teach the disciples when he says, “Whoever wants to be first must be last of all and servant of all.” And right after that, he takes a little child into his arms. You see, children didn’t have any social standing at all; they didn’t offer anything of value. Like Jesus, children were completely vulnerable. They had little to offer that the world considers precious. So, Jesus was telling his disciples, all those things that make you a success in the world (drive, ambition, power)—you’re going to have to let that go.

St. James picks up on this idea in the epistle this morning. He says, “where there is envy and selfish ambition, there will also be disorder and wickedness of every kind.” It’s a wonderful notion, and as I look back on my own life, it’s amazing how disorderly and chaotic my own appetite for recognition is. Once you start down that road, it’s hard to find an end. But the gospel tells us something else about that day. While Jesus was trying to explain that he was giving up his life for the life of the world, the disciples couldn’t understand. In fact, Mark says that “they did not understand what he was saying and were afraid to ask him.”

James suggests that our selfish ambitions will lead us to chaos. This gospel story today sort of reminds me of the Tower of Babel. Jesus is trying to talk with the disciples about the work of the Cross, and they’re having a completely separate discussion about their ambitions. And even their language has failed the disciples, because they don’t even trust Jesus enough to ask him what he means. Jesus was trying to tell them that there are hard times ahead, and they were afraid.

I’m reminded of something one of my favorite poets, Wendell Berry, once wrote: “Two epidemic illnesses of our time—upon both of which virtual industries of cures have been founded—are the disintegration of communities and the disintegration of persons. That these two are related (that private loneliness, for instance, will necessarily accompany public confusion) is clear enough…. What seems not so well understood, because not so much examined, is the relation between these disintegrations and the disintegration of language. My impression is that we have seen a gradual increase in language that is either meaningless or destructive of meaning. And I believe that this increasing unreliability of language parallels the increasing disintegration, over the same period, of persons and communities.”

So, I want to circle back to an idea I talked about earlier. I told you that in February of 1964, Muhammad Ali proclaimed “I am the greatest.” He said this as he was preparing to fight Sonny Liston for the heavyweight championship. At that time, he had won the Olympic gold medal in boxing and had never lost a professional fight. Ali would defeat Liston and become the heavyweight champion.

But life would knock Ali around a bit. In 1967, as a result of his protest against the Vietnam War and refusal to serve, he was stripped of his title. He could not fight for three years, three of the prime years of his career. He fought again for the heavyweight title in 1971 against Joe Frazier and he lost. He would fight Frazier again in 1974 and regain the title. He would lose the heavyweight championship again in February of 1978 to Leon Spinks. And that year, Ali said something very different from the braggadocio of his youth when he proclaimed himself the greatest. That year, Ali said, “Service to others is the rent you pay for your room here on earth.” Ali had been knocked around by the world, and he kept getting up, but he had come to a deeper understanding. “Service to others is the rent you pay for your room here on earth.”

Something very similar would happen with the disciples. They would get knocked around a bit. They would lose their rabbi, their teacher, and their Messianic dreams. Jesus would be hung on a tree like a scarecrow, and they would run away and betray him. They would look deeply into themselves and feel shame at their cowardice. And yet, they kept coming back. They would spread the gospel to Syria and India, to North Africa and Asia Minor, to Persia and Ethiopia, and even to Rome, the heart of the Empire. And Church tradition teaches that these same men, these knuckleheads I spoke of earlier, would each die a martyr’s death. They would become great—great Saints of the Church—but not in any way that they had imagined. They would come to realize that “Service to others is the rent you pay for your room here on earth.”

And I think most of us have learned the same lesson. This pandemic has knocked most of us around a bit. Most of us have been knocked around by life, sometimes knocked down. We’ve suffered losses, and we’ve had our hearts broken—maybe the loss of a loved one, a parent or a child, or we’ve seen our dreams dry up and blow away in the wind of disappointment. We wear those scars.

But you know, my father used to tell me, “Anybody who doesn’t have any scars, well, they never found anything worth fighting for.” The question of who’s the greatest, or a life lived listening to the siren song of our own selfish ambitions, that’s not even a fight worth winning. But a life lived struggling against my own ego in service to others, a life lived so that our brothers and sisters might know a better life—as Jesus taught us, that’s a fight worth dying for.

Amen.

James R. Dennis, O.P. © 2021