The only preparation which multitudes seem to make for heaven is for its judgment bar. What will they do in its streets? What have they practised of love? How like are they to its Lord? Earth is the rehearsal for heaven. The eternal beyond is the eternal here. The street-life, the home-life, the business-life, the city-life in all the varied range of its activity, are an apprenticeship for the city of God. There is no other apprenticeship for it.

I found this wonderful reflection in today’s reading from Celtic Daily Prayer. While our churches do a wonderful job of many things, I think they often neglect a critical aspect of their role: the Church must prepare God’s children for their death. Our lives here are very short, some far too short, and the Church must not overlook the essential function of bracing people to spend eternity in the presence of the Eternal.

In part, I think the Church has allowed people to carry on with several deeply flawed paradigms. When we think about our deaths, if we think about them at all, many have a sort of childish view of paradise. We might imagine an antiseptic place where everyone sits around on clouds, playing harps and admiring our bright, shining white robes. Or we sometimes picture a sort of Big Rock Candy Mountain, like recess in elementary school with lots of playing and big mounds of ice cream. While these metaphors are culturally ingrained, we won’t get very far travelling down those roads and they don’t really compel us to do very much.

Part of the reason these images don’t impel us toward conversion is another paradigm we have worked with for so long that it has lost its impact. Too often, the Church has viewed our lives here on earth as a sort of pass/fail examination. We have tacitly approved an understanding that upon our deaths we will face God’s judgment, and will then be directed to either Door Number One or Door Number Two. By the time we face the examination, however, it’s already too late to do anything about it.

If we have been “good” we will go to heaven, and if we have been “bad” God will consign us to the fiery lake for all time. The trick, therefore, lies in avoiding the really bad sins, and trying to rack up enough bonus points so that the Lord will (perhaps reluctantly) give us a room in His eternal home. In certain quarters, the Church has really stressed this vision of the afterlife, particularly focussing on that conduct which will result in our banishment to Hell. This paradigm, of course, rests upon a foundation of fear rather than genuine conversion of our hearts. (My father used to refer to that sort of faith as a kind of “fire insurance”.)

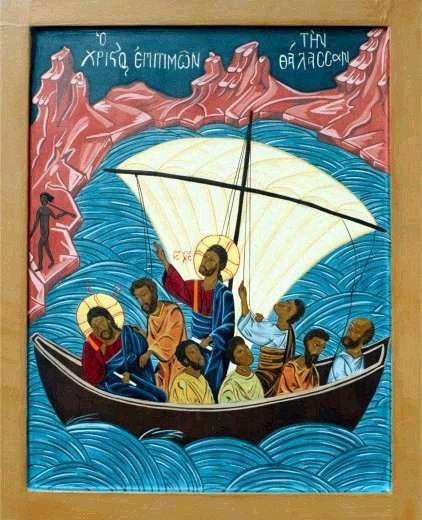

Now, there’s nothing that’s stunningly wrong with any of these traditional metaphors. I think, however, we may treat them too simplistically, and may have overlooked the metaphorical nature of this truth. It’s kind of like an icon, which may offer us a genuine pathway into a spiritual reality. But when we’ve become too attached to the icon itself rather than the spiritual insight it offers, the icon can become an idol.

The reading today suggests another approach. Rather than our lives being a kind of mine-field we must avoid to pass the test, the reading suggests that we view this life as a place to learn how to live in heaven. Today, we are each rehearsing for eternity: we are learning how to love, how to give fearlessly, learning compassion, learning forbearance, and learning how to imitate Christ.

There’s a wonderful old spiritual exercise in which we try to imagine our time with the Father in paradise. What parts of our lives just don’t seem to fit there? What attachments or addictions will I have to release for my life in heaven to make sense? Will that bit of gossip I found so interesting in the lunchroom move me closer to God’s presence or further away? That old resentment I held onto, will that stick out like a sore thumb when I’m bathed in the light of God’s presence?

The passage teaches: “The eternal beyond is the eternal here.” Jesus put it a little differently, saying “The kingdom of God is within you now.” Luke 17:21. Both passages reveal a deep, spiritual relationship between how we live today and the reality we’ll encounter in the afterlife. Mother Teresa noted that relationship when she said, “Our life of poverty is as necessary as the work itself. Only in heaven will we see how much we owe to the poor for helping us to love God better because of them.”

The Church must again take seriously its role in preparing us for our deaths, and we must take that preparation of ourselves as our sacred and solemn work. Paraphrasing Billy Graham, our home is in heaven; we’re just travelling through this world to get there.

May the peace of Christ disturb you profoundly,

James R. Dennis, O.P.

© 2012 James R. Dennis