Now he is comforted here, and you are in agony. Besides all this, between you and us a great chasm has been fixed…. (The full readings for this morning can be found here.)

In the name of the Living God, who is creating us, redeeming us, and sustaining us.

Well, good morning, everybody. So, in today’s gospel we encounter a man who’s having trouble with the afterlife and is concerned for his family. Whenever I hear this story, I think about a family we knew back in West Texas, the Beauchamp brothers.

Now, they were not nice people. In fact, everybody in the whole county knew the Beauchamp brothers. In business they were crooked, mean and cold-blooded. Well, one day, the older brother, Howard Beauchamp, he up and died. The younger brother, Ronnie, wanted to make sure that Howard got the finest funeral there had ever been in the county. He went down to the funeral home and bought a fine cherrywood coffin with silver hardware. Then he went to go see the minister.

The little church there was not doing so well. In fact, it was kind of falling apart at the seams. The air conditioner was old and tired, and the roof struggled to keep out the rain. Well, Ronnie Beauchamp, he went to the minister, and he offered him the Devil’s own bargain. He said, “Pastor, I will give your church half a million dollars if you will preach my brother’s funeral and tell everyone he was a saint.” Well, this was a real conflict for the preacher, because the church really needed that money, but he couldn’t lie from the pulpit.

So, the day of the funeral came around, and the whole town was there as the minister began to preach the funeral sermon. He said, “The man you see in this coffin was a vile and debauched individual. He was a liar, a thief, a bully, a great sinner, and he broke his mama’s heart. He destroyed the fortunes, careers, and lives of countless people in this county, some of whom are here today. This man did every dirty, rotten thing you can think of.”

“But, the preacher added, … compared to his brother, he was a saint.”

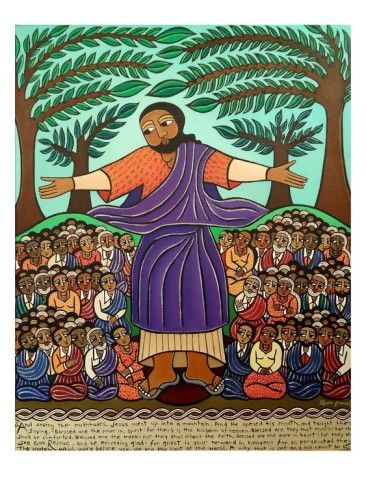

Now, before we go any further, I want to make a couple of things clear. The passage we are reading isn’t a theological guide about how to get to heaven or how to avoid hell. This passage is one of Jesus’ parables—a riddle or a fable. So, I don’t think the rich man went to Hades because he was rich. And I don’t think Lazarus went to heaven because he was poor. But I do want us to start thinking this morning about the various chasms we encounter: chasms that separate us from each other, the gulfs between us and God—the chasms we come upon, and the chasms we help create.

One of the first places we notice a gap, or a distance, is between the circumstances of these two men. We are told that every day, the rich man ate luxurious meals, and he wore fine linen and purple. On the other hand, we can imagine Lazarus in rags, and we’re told he’s covered in sores. He’s also starving, and dreams of eating even the crumbs or scraps from the rich man’s meals.

And although their lives were very different, they did not live far away from each other. In fact, Lazarus lived just outside the rich man’s gate. But we get the feeling the rich man never noticed Lazarus. In fact, I get the impression that the rich man had become quite adept at ignoring Lazarus at the gate, a kind of studied disregard, a well-rehearsed apathy. So, their lives on earth were very far apart; they were separated by a great economic and social chasm.

Then, when the two men die, we have one of those classic reversals of fortune that Luke loves. It’s already happened right from the outset of the story. You see, we know the name of the poor man in the story—his name is Lazarus, which means God’s help. We don’t, however, know the name of the other character; he’s just some rich guy. That’s not how things normally work. We remember the rich and the mighty, and too often the names of the poor and the hopeless are forgotten.

But when their earthly lives are over, the angels carry Lazarus to the bosom of Abraham. In other words, he has a place of peace and comfort and honor among the righteous dead. The rich man, however, finds himself being tormented in Hades. There’s a considerable distance, a chasm, between their circumstances. But even from the fiery pit, the rich man doesn’t seem to recognize his new situation yet. He’s still treating Lazarus like a slave. You see, the biggest lie the devil ever told us is that some lives are worth more than others, that some people are more important than others.

The rich man asks Abraham to send Lazarus with just a bit of water on his finger to ease the rich man’s suffering. Once again, here’s that Lucan reversal of fortune. Abraham tells the rich man: “Child, remember that during your lifetime you received your good things, and Lazarus in like manner evil things; but now he is comforted here, and you are in agony.”

The bigger problem, Abraham explains, is that vast chasm between Lazarus and the rich man. Now, maybe Jesus was trying to tell us that heaven is a long, long way away from hell, but I don’t think so. I think the distance between Lazarus and the rich man is simply the echo and amplification of the separation the rich man created while they were alive. In other words, to borrow an idea from Charles Dickens, they wear the chains they forged in life. Jesus reminds us that there is a deep and profound connection between how we live in this life and how we live in the next life.

So, what are we supposed to do with this passage? What am I supposed to do about the homeless man that I drove by on my way to church this morning? Am I supposed to give him a dollar? Buy him a meal? Pay for him to spend a night in a hotel room? If I do that, will Jesus let me into heaven?

I think the very last thing Jesus wanted to do in his parables was to give us easy answers to these questions. I think we were meant to struggle with this issue, to learn to listen to Moses and the prophets. I also think we have to find a way to close the tremendous gaps between ourselves and our brothers and sisters. We all know about the terrible gap of wealth inequality, and we saw the political distance widen in this country after Charlie Kirk was killed and both parties clawed at each other desperately for a spot on the moral high ground

My friends, as Doctor King warned us, “We must learn to live together as brothers and sisters or perish together as fools.” We know about the chasm between God’s children. I think the biggest chasm I have to struggle with every day is the gap between the man I am and the man I want to be, the distance between the life I’m leading, and the life Jesus wants for me.

I think the first thing is that we notice how deeply, how profoundly, God cares for the poor. This morning, the Psalmist tells us happy are those:

Who give justice to those who are oppressed,

and food to those who hunger.

The Lord sets the prisoners free;

the Lord opens the eyes of the blind;

the Lord lifts up those who are bowed down.

A friend of mine puts it a little differently. He likes to tell me that no one gets into heaven without a letter of recommendation from the poor.

Secondly, I think we have to find a way to bridge the gap between us and the broken-hearted of this world. We must find a way to reach across to those who are hungry, to those who live in hopelessness. And we’ve got to quit asking whether they deserve our help, our charity. Quite frankly, that is none of our business. God will figure that out.

I do believe charity is important, and yes, the rich man fails to tend to, or care about, the needs of Lazarus. But there was a sin that came before that, an earlier fault that made all the others possible. He didn’t even notice Lazarus. He didn’t notice the man at his gate. I don’t want to think about the number of times I’ve turned my glance away from the homeless and the poor. And the failure to notice them robs us of any chance we have to make a difference in their lives, to make a friend. So maybe we should begin by noticing them, and I mean this quite literally, for the love of God, notice them. Maybe if we go out of our way, just a little bit, we might learn to share our resources, and more importantly, to share our hearts. Amen.

James R. Dennis, O.P. © 2025