For you were called to freedom, brothers and sisters; only do not use your freedom as an opportunity for self-indulgence, but through love become slaves to one another. For the whole law is summed up in a single commandment, “You shall love your neighbor as yourself.” If, however, you bite and devour one another, take care that you are not consumed by one another. Gal. 5:13-15.

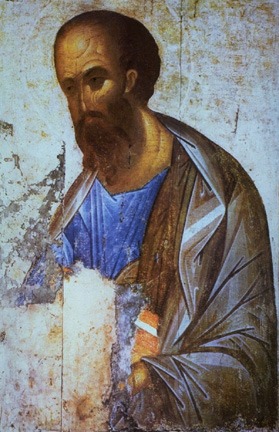

Today’s reading from the Daily Office offers us a glimpse of St. Paul’s notion of Christian freedom. Earlier in the passage, Paul says that Christ has set us free for freedom. Gal. 5:1. Paul notes that Christ has freed us, not only from the yoke of the Law, but also from sin itself.

Generally, we think of being freed from some sort of difficulty (financial debt, addiction, or a broken heart). Jesus has not only freed us from the law, He has freed us for a new relationship with the Father. Thus, St. Paul tells us our new freedom does not liberate us for self-gratification. If that were so, we would simply trade one set of chains for another.

St. Paul’s next move is somewhat surprising and offers us one of those paradoxes that we so often encounter in Christianity (a virgin birth, Jesus as fully divine and fully human, loving our enemies, etc.). Paul tells us that Christ brought us liberty so that we might become “slaves to one another.” We might well ask, “What kind of freedom is that?”

St. Paul argues that the contrary view of freedom (absolute liberty devoted to selfish goals) leads to an “eat or be eaten” way of living. He says, “If, however, you bite and devour one another, take care that you are not consumed by one another.” His language here conjures up images of wild animals tearing each other apart. (I’ve certainly been present at dinner parties which would suggest that Paul was right.) We have too often demonstrated the capacity for greed, humiliation, violence and making a way for ourselves on the backs of others. Paul is right; we consume each other.

St. Paul offers us another way: the Way of the Cross. He tells us “the only thing that counts is faith working through love.” Gal. 5: 6. Paul believes this new relationship with God compels us toward a life of charity and compassion. This new relationship with Christ draws us into a life of serving each other. There, we will encounter the freedom to be the sort of people God intended us to be. Stated another way, Jesus freed us to become the Church, His mystical body. Beyond compliance with a set of rules and beyond the “righteousness trap”, St. Paul calls us to a life of devoted service to God’s children.

That life of devotion, of self-denying love, constitutes the essence of the Christian life. Saint Paul does not see a life in community, spent in the service of God’s children, as the best sort of Christian life. Rather, he sees it as the only life than can authentically be called “Christian.”

God watch over thee and me,

James R. Dennis, O.P.

© 2012 James R. Dennis