All rational creatures have their own vineyard, their souls, their wills being the laborers appointed to work in them with freedom of choice, and in time, that is, for as long as they live. Once this time is past they can work no more, whether well or ill, but while they live they can work at their vineyards in which I had placed them. And these laborers in the soul have been given a strength no devil or any other creature can take from them unless they choose; for their baptism made them strong and equipped them with a knife of love and virtue and hatred of sin.

All rational creatures have their own vineyard, their souls, their wills being the laborers appointed to work in them with freedom of choice, and in time, that is, for as long as they live. Once this time is past they can work no more, whether well or ill, but while they live they can work at their vineyards in which I had placed them. And these laborers in the soul have been given a strength no devil or any other creature can take from them unless they choose; for their baptism made them strong and equipped them with a knife of love and virtue and hatred of sin.

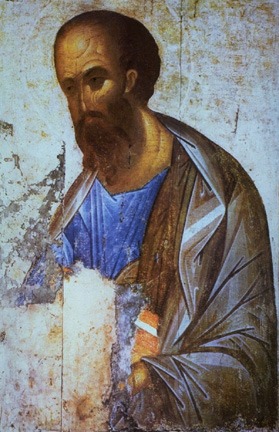

St. Catherine of Siena, from the Dialogue of Divine Providence

I found this wonderful little reflection in Fr. Robert Wright’s work, Readings for the Daily Office from the Early Church. It’s particularly meaningful for me because Saint Catherine of Sienna was also a member of the Dominican Order. She lived from 1347 until 1380, is one of the two patron saints of Italy, and has been named a Doctor of the Church.

Although a mystic, she was also a theologian and a Scholastic philosopher. She lived during the time when the black death ravaged Europe. Her parents had 25 children, although only about half of them survived to adulthood. She worked very hard to bring unity and peace to the Roman Catholic Church, deeply loved the poor, and both befriended and occasionally chided Popes and clergy. The Dialogue of Divine Providence treats the whole of our spiritual lives as a series of colloquies between the Father and the human soul.

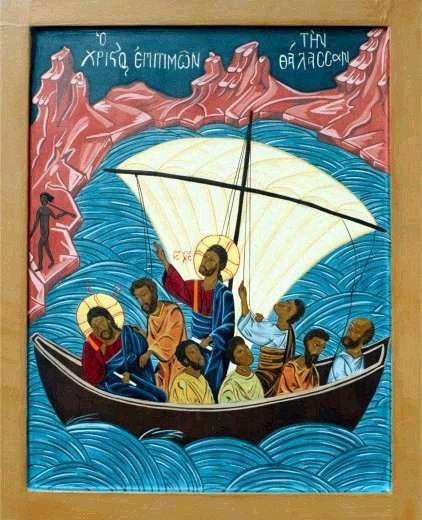

In this profound passage, St. Catherine compares the soul to a vineyard. We might immediately think of Jesus’ description of us as branches of a vine. See John 15:5. We might also think of the parable of the vineyard workers set out in Matt. 20:1-6. With regard to this vineyard of the soul, Catherine observes that we have been given a specific time within which to complete our work. Once our time is past, she observes, we “can work no more”. St. Catherine reminds us that our time is relatively short, and that we must be about our spiritual work while we can.

To accomplish this work, our Father has provided us with powerful tools: the sacraments (and baptism in particular). Catherine compares them to a knife (such as one might use to prune a vine), but this is no ordinary blade. God has provided us with a “knife of love and virtue and hatred of sin.” With these, the Almighty has equipped us to work in the soul’s vineyard. Important work awaits you and me, and The Lord has given us tools that neither the devil nor anyone else can take away from us without our consent. For the work of the soul, we have everything we need.

God watch over thee and me,

James R. Dennis, O.P.

© 2012 James R. Dennis